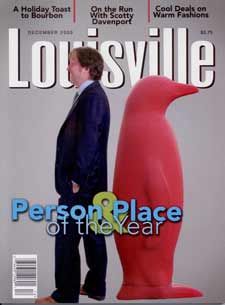

The Green Building co-owner Gill Holland

voted Louisville Magazine's

"Person of the Year"

By Josh Moss

Photos by John Nation

Holland’s Focus

Despite a gloomy economic climate, Gill Holland pressed forward with several socially conscious projects this year. Not content to sit still, he's planning more for the future.

Despite a gloomy economic climate, Gill Holland pressed forward with several socially conscious projects this year. Not content to sit still, he's planning more for the future.

On this day, his pulpit is a lectern inside a University of Louisville business-school classroom. His corduroy blazer lies over the back of a chair. He has removed the green designer tie from around his neck and unfastened a couple of shirt buttons, revealing his thick chest hair. As usual, his surfer-meets-mad-scientist brown locks are shaggy. This is how Gill Holland delivers his sermon. “What are you doing to make this city better?” Holland asks the congregation of undergraduates. “How do we make Louisville the coolest place in America?”

Holland recites a synopsis of what locally is becoming his familiar backstory: Childhood in North Carolina. Law school. Paris law firm. Ditching that to pursue producing movies. New York. Marrying Augusta Brown, the daughter of a former Brown-Forman CEO. Moving to Louisville less than four years ago.

He mentions how, during the previous week, he attended a green-energy forum at the White House, which draws some ooohs. “I’m glad some people outside the state are hearing about us,” one student says. At the conference, Holland notes, U.S. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu said, “Inaction will be horrendous.” (Some national studies report that Louisville has the nation’s fifth-largest carbon footprint, our reliance on coal and lack of public transportation being huge reasons why.) “I actually think the green boom is going to take us out of this recession. America is so far behind the rest of the world, and Kentucky is behind so much of America,” Holland says. “This is the industrial revolution of our time. Sometimes, it’s just hard getting people to see long term.”

For Holland, not so much. And his capacity to project long term — along with his enthusiasm to challenge the rest of us to consider our city’s future — is one of the reasons Gill Holland is Louisville Magazine’s 2009 Person of the Year. During a year of economic stagnation and a cautious business climate, he has plowed forward with socially conscious projects. “Pretty big year for me, 2009,” Holland says.

Among the highlights: The trendy 732 Social, a restaurant that opened in 2009 inside the Green Building, which Holland owns with his wife, on East Market Street. He penned a children’s book that has raised $20,000 for the Speed Art Museum’s interactive gallery for kids. There’s a CD: All proceeds from the recently released Louisville Lullabies, which features local musicians, will go to the Home of the Innocents, a local refuge for children. Meanwhile, under his guidance, several of the East Market Street properties he and his wife own with other investors are under construction and giving shape to the neighborhood, which this year added NuLu — Holland’s SoHo-inspired nickname for the area — to its street banners. An inaugural NuLu Festival christened the art-district concept.

“All in the middle of the Great Recession,” Holland says. “Pretty amazing.”

Today, his pulpit is the third story of the Green Building, the more-than-100-year-old structure the Hollands purchased for $450,000 and renovated for more than $1 million. This is his headquarters. Exposed, crisscrossing beams of partially recycled wood are attached to the soaring ceiling, which gradually slopes from the back of the building to the front windows. Natural light floods the space. There is an elevator, but Holland says he has considered posting a sign: “It’s an effing green building. Take the stairs.” A downstairs “green wall,” which he says is the state’s first, went in this year and has sedums and ferns growing from it. Eighty-one solar panels help power the place, which Holland says is 72 percent off the grid and has prevented 350,000 pounds of carbon dioxide from entering the atmosphere in its first year.

In his office, Holland is relaxed behind his messy desk, his caffeine fix coming in the form of a can of Diet Coke. “People are going to look back at this building and scoff that we’re not 100 percent off the grid,” he says. “They’re going to look at our clunky solar panels like they do old cell phones.

“The reality is that all the money you spend on green stuff, it pays for itself. Maybe it’s a 20-year return,” he says. “People were laughing a year ago when we put in $100,000 worth of solar panels. If I had that $100,000 in the stock market last summer (2008), it’d now be worth about $58,000.”

Holland recently turned 45 — or “halfway to 90,” as he likes to put it — and a few weeks ago his wife gave birth to twins, bringing the total number of kids in the family to three. The gray hairs have crept into his reddish sideburns, and the dark circles under his eyes have become a permanent feature. His philosophy on life: “Leave it greener than it was when you got here.”

The time he spends reading to Cora, his almost three-year-old daughter, inspired Louisville Counts, the book he wrote and got local artists to illustrate. He’s now working on a version for New York, where he lived for 13 years, and he is two letters shy of completing L is for Louisville, an alphabet book. “The kids are going to be the ones who save us, so we have to get to them early,” Holland says. He’s made the rounds with FLOW: For Love of Water, a documentary he produced, even screening it for elementary-schoolers.

Another idea came while honeymooning in South Africa. He and his wife were on a safari learning about the social weaver, a bird that constructs giant shared nests. “They can invite all their friends over,” Holland says. He told his wife it would be an amazing name for a restaurant, and when they decided the Green Building needed a street-side eatery, the Hollands went to the owners of Basa to create the Sociable Weaver, which eventually became 732 Social — turning a profit in its first year despite the shaky economy. Jayson Lewellyn was involved from the beginning and is now 732 Social’s chef-owner. (The Hollands are the landlords.) “When I met Gill, I could tell he wasn’t from Louisville,” Lewellyn says. “He’s got a faster pace. It’s difficult keeping him still and focused on one thing for more than 10 minutes.”

Down the street from the Green Building, construction crews are already gutting several structures in an 11-building complex that the Hollands and other investors purchased in 2008 for $5 million from Wayside Christian Mission. By 2012, Holland says, there will be offices and shops and restaurants and wine bars. Creation Gardens plans to move in across from the Green Building. A public market will open. When all’s said and done, Holland says, he and other investors will have dumped upwards of $25 million into the neighborhood. “I love things happening yesterday,” he says. “They’re always like, ‘Gill, let’s concentrate on one building at a time.’ I’m like, ‘No, let’s do all four.’”

Joe Reagan, Greater Louisville Inc.’s president and CEO, credits the vision. “With Gill and Augusta coming in and recognizing the potential and jumping in with their full enthusiasm,” Reagan says, “they’ve secured the future for East Market Street in a way that wouldn’t have happened without them.”

The most public resistance to Holland’s actions in the past few years came from Wayside. The homeless shelter, which Nina Moseley runs with her husband, couldn’t launch a long-planned Market Street expansion last year because, for one thing, Holland spearheaded a petition to make Wayside’s buildings landmarks, essentially making it too expensive for the shelter to build or renovate in the area. “It was never about pushing Wayside out,” Holland says now. “It was, ‘If you need to expand, don’t tear down these beautiful buildings.’”

Moseley expressed frustration when the petition drive succeeded, but looking back now, she doesn’t blame Holland; rather, she points to the East Downtown Business Association, which she says did not honor an agreement it made earlier that would have permitted Wayside to expand. “Gill’s the one who gathered the signatures and filed the petition to the Landmarks Commission,” Moseley says. “Gill Holland has a vision for East Market Street. We couldn’t afford to fit in with our properties landmarked.

“He has the resources to not do anything half-baked. I think it’s unfortunate we lost our home of 35 years, but I have confidence he’s going to make that a wonderful area.”

Holland wants to market the city with T-shirts that say “Louisville” on the front and “Staff” on the back. Both he and Steve Wilson, co-owner of 21c Museum Hotel (see page 52), say they’d like to brand our town as the “City of Arts and Parks,” a slogan Holland has trademarked. “I go back to the Confucius ideal that a city with great culture attracts power and wealth,” Holland says. “There’s a reason Seattle has companies like Microsoft. The 20something, creative hipster wants to go to a city that has clean air and nice parks. We have tons of nice parks. We don’t have the clean air, and that’s a problem.

“We need to get the next Google. That’s going to be much more important to our long-term well-being than getting another convention. We’ve had so many short-term plans. What’s the 50-year plan? We need to look into the future. It’s hard when you’re in the middle of a great recession, but we must.”

Holland says light-rail transit systems should exist between Louisville and Fort Knox and Frankfort, Ky. That’s just part of the picture. Also: No passenger cars downtown; rapid-bus transit would transport people instead. Parking garages would become offices. Mountaintop removal would end. Local farmers would provide meals to schools, jails and government buildings so the food’s not coming off a truck traveling cross-country. An entrepreneurial, tax-free zone downtown would attract start-ups. (“Right now, we’re trying to get existing companies to move,” Holland says. “That’s like trying to get a girl who already has a boyfriend to come date you.”) “In a perfect world, the city would be able to put out some kind of bond issue where low-income families — or anybody who wanted — could borrow some money, put solar panels on their roof and pay off the city bonds with the savings that they get from their LG&E bill,” he says. The Hollands have installed solar panels on the roof of their Cherokee Road home.

As Jefferson County’s unemployment rate nears 11 percent, Holland sees a potential solution: “Louisville is, in some ways, an old-school manufacturing city. We have to realize that it’s really hard to compete with other countries that pay workers $3 a day to make stuff. Until gasoline gets so expensive that the transportation of those cheaply produced goods costs more than the savings you get, we are not going to be a manufacturing city,” he says. “But we do have these big factories that make cars. Could we convert them into wind-turbine factories? In World War II, they had all those Detroit car manufacturers start making tanks and planes. And within, like, two years they were producing gajillions of tanks and planes. We could be doing that with wind turbines and solar panels within two years, and we’d have tons of jobs while also getting ourselves off the grid and less addicted to foreign oil.”

When Louisville Mayor Jerry Abramson’s term ends next year, Holland will propose to work for Abramson’s replacement as a deputy mayor of sustainability. His salary: $1 a year. “I don’t know of any other city that has a deputy mayor of sustainability,” Holland says, “but I think outside people would look and say, ‘Wow that’s a cool city.’”

Did you consider running for mayor?

“I got some fan mail. I had a bunch of people ask me to run for mayor, and I said, ‘I’m having twins,’” he says.

If there hadn’t been twins?

“I was thinking about it, yeah.”

Today, the pulpit is his green Prius with children’s books strewn across the back seat. Holland is cruising west on Main Street downtown, classical music dancing from the car’s speakers. He is wearing a bulky red-and-black sweater that his Norwegian mother knitted. As he passes under I-64 ramps on his way to Portland, he says, “Here we have the boundary, the freeway cutting up our city, separating us from our neighbors.”

Near some warehouses on 15th Street is a home from the 1880s that the Hollands recently purchased for $25,000, their 16th property in town. “Cheaper than buying a car,” Holland says. He doesn’t yet have the keys and hasn’t been inside. The house is off plumb; it sort of looks like a two-story slice of pie that tilts to the side. The front yard is unkempt. Spray-painted boards cover what used to be windows, and the white bricks are discolored. From the second floor, downtown’s skyline will be visible. “I can see how beautiful this could be,” Holland says. The owner was going to tear it down, but Holland saw architectural and geographical potential. “I think this property is the gateway to Portland,” he says. “This whole block could be a cool arts scene — call it the Warehouse District.”

A Portland project is on the horizon?

“Yeah,” he says, “say, 2012.”